You can read Healing for free, and you can reach me directly by replying to this email. If someone forwarded you this email, they’re asking you to sign up. You can do that below.

If you really want to help spread the word, then pay for the otherwise free subscription. I use any money I collect to increase readership through Facebook and LinkedIn ads.

Thank you for reading Healing the Earth with Technology. This post is public so feel free to share it.

I am at a loss for what to write about climate change this week. It’s Superbowl Sunday, and I’m bummed that Josh Allen missed the cut both at Arrowhead and at Pebble Beach. I hope he’s done with his vacation now and is working on D-reads for next year instead of improving his short game. I’m also rather pissed that not a single Bills defensive player was selected for the Pro Bowl. But there’s next year: 30 years is too long to wait.

For your entertainment, I thought I’d add to my somewhat tongue-in-cheek “pseudo-political” thread, which I last covered concerning COVID and government response. The phrase transposes what some have called “pseudo-science” (exploiting false scientific arguments for political ends) by explaining political views in terms that we can understand scientifically. I’ll get to that at the end, with (of course) data, but I thought I’d give a shortened version of an authoritative political discussion of science. This excerpt from the podcast “Politicology,” features Fortune 40-under-40 (Government & Politics) former Republican Ron Steslow and former Republican political consultant Mike Madrid. Both were co-founders of The Lincoln Project but have left for greener pastures. Mike, in particular, is my kind of guy: Regular listeners will recognize that he “eats numbers for breakfast”. In a recent installment of The Weekly Roundup (Episode 102), they talked about the politics of COVID science, with an eye toward the Joe Rogan-Spotify brouhaha. Here’s the salient section, starting at about 35 minutes in. It’s worth a read or a listen-to.

Ron Steslow: One of the biggest controversies we’ve seen over the last couple of weeks is the Spotify Joe Rogan saga. In December, Joe Rogan had two vaccine skeptic guests on his podcast, Dr. Robert Malone and Dr. Peter McCullough. Malone then claimed that COVID vaccines do not work and that a third of the population is basically being hypnotized into believing that vaccines work using an unfounded theory called “mass formation psychosis”. McCullough claimed that previously infected people have permanent immunity to COVID, despite the reinfections that occur. After the interviews aired, 270 health care workers wrote an open letter to Spotify, who has the exclusive streaming rights to Rogan’s podcast, to fight misinformation on the platform. And then this boiled over when polio survivor Neil Young demanded that his music be removed from Spotify, specifically because of their partnership with Rogan and because he believed the show spreads false information regarding COVID 19 and vaccines. And since Young made the request, Crosby Stills & Nash, Joni Mitchell, Nils Lofgren (of the E Street Band) have also asked for the music to be removed. Roxane Gay and Mary Trump have removed their podcasts from the platform. Brené Brown announced that she was pausing the release of her two Spotify exclusive podcasts to learn more about Spotify.

Spotify has a misinformation policy. After the pushback, Spotify CEO Daniel Ek released the platform’s approach to COVID 19 rules publicly. He said that the policies have been in place internally for years but are now publicly available. He also announced that they would add a content advisory to any podcast episode that includes a discussion about COVID 19 and will direct listeners to a dedicated COVID 19 hub.

In a video shared on Instagram, Rogan said he wasn’t trying to promote misinformation and said that he would try to book more experts with differing opinions “after I have the controversial ones”. Rogan also questioned how the understanding of what is “misinformation” has changed over the course of the pandemic, and this is the part of his response video that I found particularly compelling, and I sympathize with. He said. “Many of the things we thought of as misinformation just a short while ago are now accepted as fact. For example, if you said eight months ago, ‘If you get vaccinated, you can still catch COVID, and you can still spread COVID,’ you would have been removed from social media. They would ban you from certain platforms. Now that’s accepted as fact. If you said, ‘I don’t think cloth masks work,’ you would be banned from social media. Now that’s openly and repeatedly stated on CNN. If you said, ‘I think it’s possible that COVID 19 came from a lab’, you would be banned from many social media platforms. Now, that possibility is on the cover of Newsweek.” So I sympathize with this response because I think he’s emblematic of people’s challenges keeping up with the changing information, especially around COVID. But in a world where we want people to discuss things openly to explore heterodox ideas, the answer increasingly seems to be more and more censorship.

This saga has renewed that debate. Ek stressed that Spotify doesn’t want to become a content censor and that he is committed to supporting creator expression in an opinion piece for Time magazine. Former USA Today editor-in-chief Joan Lipman argued that this argument falls short. In this case, it’s the same argument that Facebook and Google have made that they distribute content but aren’t responsible for that content. Her argument is that this line of thinking isn’t sufficient when Spotify paid $100 million for the exclusive rights for the podcast. It’s a publisher, so you know, to me, I’m most curious about the ‘censorship-versus -content moderation’ debate that is now seeped from social media companies or Big Tech to now our podcast and spoken word domain. There’s a bunch of different ways we can take this and, you know, I’ll put my cards on the table. I’ve been a Joe Rogan fan for a while, and that doesn’t mean I like all the guests that come on his platform or that I look to them as a source of truth, but I definitely look to the programming as a source of curiosity for me and a way to explore things I hadn’t been thinking about before.

…

Mike Madrid: I think there’s a lot of false logic at play here, and let me explain why. My view is that the quote you gave from Joe Rogan is the perfect argument for a license to say whatever the hell you want in a way that establishes faux credibility with everybody else. Are scientists wrong? Yes, that is literally part of the scientific method that is part of the process is being wrong. You test your hypothesis, and you’re wrong. That does not mean that a podcaster [is the same as a scientist]. They don’t have the same epidemiological expertise as a Dr. Fauci, and I’m not making a case for the personalities. I’m trying to draw a correlation here. The problem with today’s society is we are continually seeking a license to say, “I am as much of an expert because of my opinion as everybody else.” That explains Joe Rogan. The great tweet I saw is, “What’s the big deal about Joe Rogan?” Well, in the seventies, I had a friend who had a 27-year-old big brother who smoked pot all day and was talking about how the Mayan civilization actually created cellular phone technology. Right. Like the “Joe Rogans” have always been there.

This guy’s just got a platform, you know, selling and talking a bunch of bullshit. … Let’s not buy into this false idea that it’s equivalent to science. Science, by definition, is wrong, but you go with the best information that you have at a given time. Just because you don’t believe it doesn’t mean that you have the same credibility as somebody who has spent fifty years in this area of expertise to try to protect public health. No. Your opinion is not as valid. It’s not. We need to stop as a society permitting that and saying that. Because it’s so easy to communicate on so many mediums to so many siloed individuals, we’re seeing a flattening of expertise, a loss of it (as our friend Tom Nichols would say) where everybody who doesn’t even have any legitimate argument or space to be in is saying, “My voice is just as credible because you were wrong in the past.” No, that’s not how it works.

Ron Steslow: Yes, I completely agree with all of that. I think this is one of those situations where everybody’s right. Joe Rogan is right to issue an apology (such as it is) and tell people how he’s going to add a disclaimer and have on more mainstream guests. Explain that the views of this guest do not represent the scientific consensus or the expert consensus of experts. Right? I think Spotify is right to stand behind not just Joe Rogan but their investment as a for-profit entity. I think that the podcasters and the content creators pulling their material from Spotify are perfectly within their rights and right to do what they think is right in this situation. I think all of those things are good and healthy. Here’s where I have a little trouble. The White House has weighed in, with press secretary Jen Psaki saying, “Spotify has taken positive steps, but there is more that can be done.” … What is the White House’s role? Should the White House even have a role in this news event?

Mike Madrid: It has the bully pulpit, and I think it should be used. Look, I think that I agree with you to a certain point, Ron. Where I think I might part ways is when we’re talking about matters of public health, right? There are limits to free speech. I do agree with you that everybody has a right to do what they’re doing, and they should have that right, and it should not be infringed. I do get a little queasy when I hear people putting out misinformation that is actually killing people. That to me, that’s a line. And I think it’s debatable. Even then, it’s debatable where that line is. Most importantly, where that line is, and I’m a pretty big advocate of, “More speech is better than not,” but that doesn’t mean that all speech should be permitted. You’re not seeing an 8Chan-type discussion on Joe Rogan. And if you were, would we be OK with that? Probably not. But you would see more people pulling away from it. In many ways, that’s the marketplace at work. And that’s actually why I’m interested in the Spotify discussion. We’ve talked about this a little bit before. The traditional boycott does not work, right? Companies and businesses are too flat. Their networks are too big.

Ron Steslow: It doesn’t impact them enough.

Mike Madrid: It doesn’t impact them really at all. But what it can do is it can limit future growth for a public company, which is extremely damaging. And it’s kind of what happened with Uber. The rise of Lyft was because of a social push against Uber, and that same type of thing can happen with Spotify. Joe Rogan alone is probably enough to carry Spotify, right? So it’s not like they’re trying to shut down Spotify. But you can, you know, vote with your art and move it somewhere else and say no. And if enough people do that, you can see some economic consequence at a minimum. At a maximum, you are building a different alternative place where like-minded people who do not accept this speech as acceptable go to spend their dollars.

…

The missing component here that we don’t talk about is the lack of responsibility to one another. It used to be that when somebody was pushing the boundaries of social norms, we would have a communal discussion about whether that was right or wrong. “Is Hustler magazine doing the right thing or the wrong thing?” And it becomes a real lightning rod. Now we don’t have that discussion as a community or as a nation or as a country because we’re not really one community anymore, right? So when that happens, we lack the social responsibility that a social contract required. We have to say, “Hey, maybe this is not good because it’s killing people.” Yeah, it’s getting the audience. Yeah, I can become a bigger podcaster. Yeah, maybe I can make another 20, 30 million dollars doing this. But is that worth killing a few extra hundred thousand Americans? Some people are saying, “Yeah, it is.” And I want to say, “Good for them!” But no, not good for them. Like that should be a line where we have an obligation to each other by not putting out things that are quantifiably known to be false under the rubric that, hey, maybe someday we’ll learn that it’s true when we know people are dying today. And that kind of license is the bastardization of freedom that I think our country is suffering from right now. “I have the freedom to do whatever the hell I want, as long as I get what I want out of it.” More money, more power, more listeners, more viewers, more clicks. And that is a very different place than American society has ever been in that at this moment in time.

Ron Steslow: I totally agree. I think you made a really good point, which is the idea that something might turn out to be true in the future. You’re right. It’s a perfect rationale to say whatever you want, as irresponsible as that might be. However, those things did turn out to be true, and they were heterodox views at the time. And then when those people say, “See, we were right about these things,” whether it was [that] science hadn’t caught up yet, or we had terrible messaging from authorities. Whatever the reason, those people are now validated, which continues to erode trust in the institutions that are responsible for distributing accurate information.

Mike Madrid: These are the same people that were pushing hydroxychloroquine, ivermectin, injecting bleach, and inserting a light into your …. OK, so yes, a broken clock is right twice every 24 hours. My point is this: There is nothing wrong with having a good scientific discussion, and there was disagreement in the scientific community about this. These are people that have spent their entire lives working towards this question, and the scientific method again is built on the idea that your hypothesis is wrong. But what if we did not make the mistake of putting people together and wearing a cloth mask? Would two or three or five percent more of an infection rate during some of these peaks have killed thousands of more people? Yes, quantifiably it would have. I think that is worth making that mistake. The point is, the scientists are saying, “Here’s the technology we have with a novel virus, something we have never seen before, and the cost of losing lives is worth this policy decision.” That kind of a determination from experts is far different than a podcaster who is saying, “This is what I think. And, oh, buy my ivermectin brand, because this is what I think worked. And I took it, and I got all better.”

Ron Steslow: What then? Who then had the responsibility to do things differently at the time? If you could go back in time, was it Joe Rogan? Was it Spotify? Was it the authorities? Where’s the stick? That’s my question. Because that’s where I struggle.

Mike Madrid: Well, let me say this. We know historically that a pandemic strikes the global population, usually once every hundred years. The 100th year was up, right? Obama was planning for this. We all knew that something was going to happen in my estimation. Maybe it just comes from my life and my experience, but I would rather have the government overreact in instances where there could have been a mutation that was far more contagious and far more deadly and having people prepared when we had never seen this thing before, than not. This was not simple. Look at the virus of misinformation on electoral campaigns and balloting. We’re seeing the damage that is doing. That’s not necessarily going to kill anybody directly. I can see more room for saying, “OK, let’s have that discussion,” than on something that we quantifiably know is causing death. Like, people are dying. So when that is the case, I would rather have the government overreact and then walk stuff back. To me that doesn’t undermine the credibility of government. It actually adds to the credibility of government. And just because somebody could then come back and say, “Well, see, I was right!” You were right on one thing. Out of the 50 things that you were suggesting, statistics would suggest, of course, you were going to get something right.

And so again, to me, there used to be a certain trust in institutions where people would say, “Hey, maybe they’re not exactly right, but they’re right enough and my obligation is to other people. I’m willing to make that sacrifice.” We’re not willing to do that anymore. Yeah, “I would rather have people die than be inconvenienced by putting on a mask and going into Wal-Mart. And a cloth mask does not work as much as an N95 mask.” But does it work one or two percent better? Yeah. Had 30 percent of the population that was not wearing a mask put it on to have one or two percent effects with exponential growth. Would it have an impact? Yes, it would have. So, you know, it was the best technology we had at the time, given the knowledge on something that the human species had never seen before. You make a mistake, government. Look, I’m very, very critical of government. But, people are dying!

Mike is spot on with his analysis: There's a stark warning to my readers on either side of the political median. Limiting the First Amendment is perilous. If you think that Spotify should cancel Joe Rogan because he’s spreading “dangerous lies”, then ask yourself, “Whose responsibility is it to determine truth?” [If you say “government”, I recommend a re-read of Orwell’s “1984”.] If, on the other hand, you think that career infectious disease specialist Dr. Anthony Fauci should be fired because he “has continually failed to provide Americans with accurate information about the COVID–19 pandemic and has shown distrust in the American private sector and American ingenuity” [A direct quote from the “Fire Fauci Act”], then ask yourself the parallel question: “Whose responsibility is it to define accurate information?” [If you don’t say independent scientists, then I recommend that you think again.] Note the subtle distinction between ‘truth’ and ‘accurate information’—the former is an absolute unquestioned ideal, while the latter changes with data.

I should also point out that, on both ends of the spectrum, some express the falsifiable belief that the Presidential Election did not reflect the people's will. It’s just that the “Resist” left objected to 2016, and the “Stop the Steal” right objected to 2020. I’m not suggesting that the dementia is symmetric. I’m just urging you to think for yourself and avoid amplifying trash journalism. It’s not enough to criticize others for spreading inaccurate information. It’s up to you to adopt the ethos of a journalist. Think outside the herd and forward and/or like only those pieces that you have corroborated. Politicians (of either party) are not responsible for the country’s problems—it’s up to you and me. Recall that the Constitution begins, “We the People of the United States…”

Let’s move on to the data. This week I thought I’d pull out a data source that has become fundamental to our political discourse: Polls. You’ve probably heard the soundbite on the news, something like “a third of Republicans” believe in the latest wacko conspiracy theory. If you identify as a Democrat, I’m pretty sure you think “Republicans are crazy” (even though that’s not what the data says). If you identify as a Republican, you think “maybe there’s something to that theory” (which leads down the interweb’s various rabbit holes). In any event, I’d assert that the act of polling distorts the results—If you’re an independent centrist, moderate (what I’d call myself, and what the “average” voter is, by definition), the pollster insists that you self-identify. Once that happens, tribalism sets in, and instead of listening to your thoughts, you echo the sentiments of the tribe.

Let’s look at one data point. In October 2021, The Economist (A London-based weekly) and YouGov (an internet survey company) ran a survey that concluded: “40% of Americans believe that Joe Biden did NOT legitimately win the 2020 Presidential Election”. I recommend that you sign up for a YouGov panelist account—from what I can tell, they collect personal, demographic data online, but, like most “portals” they do not independently verify identity or accuracy—you can be whomever you’d like to be. Further, they reward participants with “points” redeemable for cash or gift cards. So, as a panelist, you’re paid to complete surveys. Second, they ask multiple-choice questions based on these self-reported demographics, so I’d imagine that if you’d like to create an email as a Russian dissident and respond to survey questions about the condition in that country (and get paid for it), you could. So, with that in mind, what’s the data?

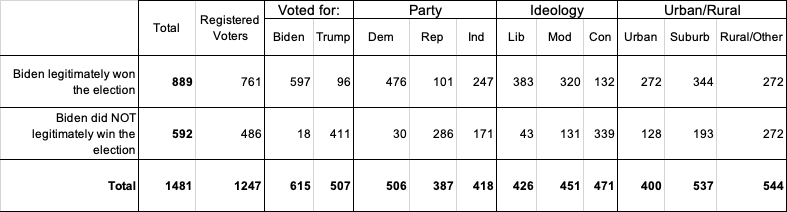

The YouGov engine sent a group of 1,500 Americans a survey that asked them to choose whether Biden did, or did not, “legitimately” win the election. Here’s what the responses looked like:

So, ask yourself a few questions (which have no correct answer):

In a partisan context, what does the word “legitimately” mean? For example, if you asked a football fan whether an unfortunate loss for their team was “legitimate”, do you think respondents would skew their answers? How do you think the results would have changed if you eliminated the qualifier?

Are 1,500 YouGov-registered Americans representative of the electorate? What additional information would you like to know to determine that the results were an accurate representation of genuine opinions.

What happened to the 19 folks that didn’t answer the question?

What about the 18 Biden voters and 30 self-identified Democrats that believe that the outcome was not legitimate? Are polls that include ~15% of non-registered voters and almost a quarter of respondents who did not report voting for either major candidate likely to be valid?

I’m not a pollster, and I’m not a statistician. The point of asking these questions is to encourage you to think about how political information is developed and disseminated, and to also encourage you to take a productive role in the process. As another favorite podcaster, Kai Ryssdal (of NPRs Marketplace and Make Me Smart) quotes Kenneth Blanchard, “None of us is as smart as all of us”.